11 Sep Wagner’s Charmed Circle

Published: The Observer 9th September 1979

Each year thousands make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth for the Wagner Festival. This year Phillip Hodson joined in Wagnermania.

The aggregate singing time for the four operas of Wagner’s ‘Ring’ – which for the audience is also the sitting time – is 14 hours 10 minutes give or take. You’re supposed to do ‘The Ring’ in the space of a week.

With intervals, the saga can last for 21 hours. ‘Das Rheingold’ takes two hours 20 minutes without a break. The first act of ‘Gotterdammerung’ alone is two hours even. For a feat of endurance you can only compare this with the fanatical audience of a mediaeval sermon.

In the art world, there is nothing to match Wagner’s ‘Ring’, even on celluloid. He simply wrote the biggest, longest, most controversial musicals ever. By the second act of ‘Siegfried’ on that fateful night, I was hanging on the edge of my seat spellbound as well as chairbound. One week later, I was hospitalised with piles; but I didn’t care. And for one with such an over-developed sense of self-preservation, this was really worrying – or as Bernard Levin put it in his New Statesman article of September 1965: ‘What am I going to do about Wagner?’

Mr Levin’s personal solution has been to exorcise his feelings by writing about Wagner in successive issues of The Times until they had to close the paper. Mine has been to spend money I can’t afford on records, tickets, books and German lessons in a clear belief that getting me knowledge will get me wisdom. If you hear my car coming down the High Street it is not Hitler’s overdue invasion of Britain but our entire family income pounding out of the stereo.

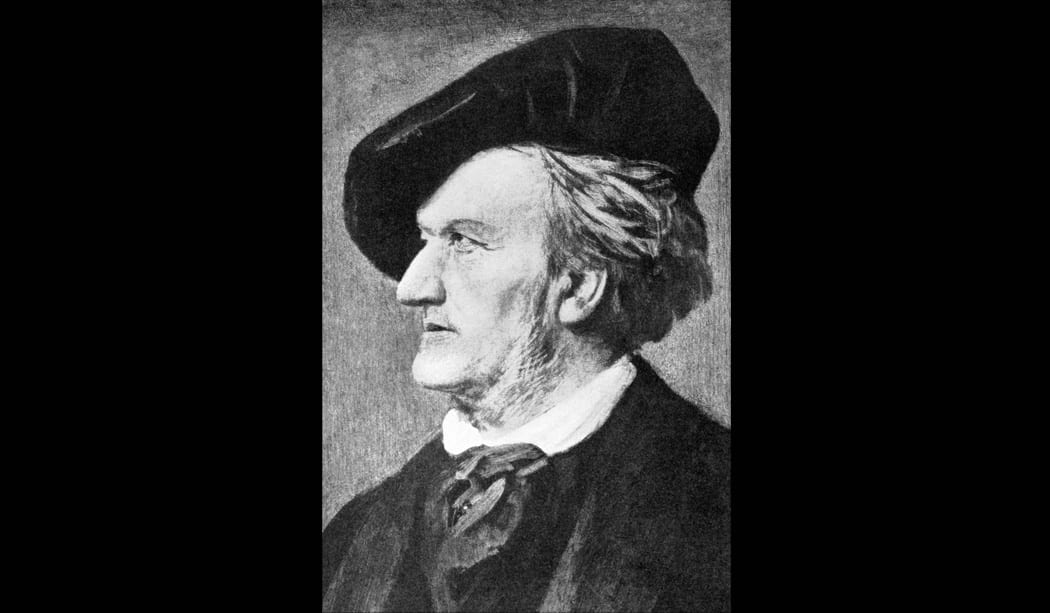

Any music can stick in the brain, says Levin. ‘But a headful of Mozart does not disturb my mind; a headful of Wagner does’. Levin and I are in excellent company. ‘We recently had a very serious conversation on the subject of Richard Wagner’, Pierre Louys wrote to Claude Debussy: ‘I merely stated that Wagner was the greatest man who had ever existed’. Baudelaire, Mahler, Nietzsche, Liszt, Thomas Mann and Bernard Shaw agreed. Shaw said that even at performances whose incompetence beggared all powers of description, even his, ‘Most of us at present are so helplessly under the spell of “The Ring’s” greatness that we can do nothing but go raving about the theatre between the acts in ecstasies of deluded admiration’.

The number of books and articles about Wagner exceeds those about any other human being except Jesus and Napoleon, or Jesus and Karl Marx (depending on how you count). Wagnerians worship their man in the way that Beethovenites or Bachians do not. Attending the Wagner Festival at Bayreuth is a pilgrimage. Levin says he has ‘never yet succeeded… in sitting through the end of “The Ring” without weeping’.

At the controversial Chereau centenary production at Bayreuth in 1976, conservative and progressive Wagnerians slugged it out with fists. It may be the worst advertisement for High Art (or it may say lots about sitting down for 21 hours) but which other classical composer can stimulate scenes of football hooliganism from an international audience of middle-class supporters?

I went to Bayreuth to try to answer this question: in effect, why are Wagner’s the greatest fanatics? Bayreuth is an utterly dull, quiet and clean North Bavarian town specially chosen by the maestro for his festival so that no one would be distracted from paying his operas their rightful due by having anything else to do during the season. They don’t. And, to this day, there isn’t.

If you can forget the presence of the US Army up in the hills making all this possible, you might think Bayreuth the uneventful twin of somewhere like Leamington Spa. However, Leamington does not have a whole cast of operas characters for street names.

Consulting your Wagnerian memory and the local A-Z you discover Siegfriedstrasse, Brunnhildestrasse, Hundingstrasse, Frickaweg, Gutrunestrasse etc – while the rest of the streets are more conventionally termed Lisztstrasse and Beethovenstrasse, giving a first impression of a sort of highbrow Disneyland.

There is no laughter in Bayreuth pubs when visitors don dinner jackets and bow ties to go Wagnering up the hill. In the shops you can buy Wagner busts, statuettes and death masks; you can eat Wagner in chocolate or marzipan to choice (‘Have another death mask, dear!’) Every bus-stop sports a poster of famous Wagner conductor Sir Georg Solti beaming his Decca-matic grin. Solti is not in chocolate, but there are boxed sets of ‘Rheingold’ and ‘Siegfried’ by Solti in record shops, chemists, furniture stores and hairdressers, on fridges, cookers and curling tongs. There is Solti with socks and Solti with shampoo and probably fish ’n’ chips with Solti if you cared to look.

The entire town feeds on the festival and its tourist trade. And the tourists feed on their texts. ‘I feel’, said Pierre Langbach of Copenhagen, an English teacher on his fifth trip to the festival, ‘as if I were back in school during exam week when everyone was scurrying around with their cribs mugging up for their special subject’.

Wagner is the supreme egotist who by capturing his audience away from home for long periods of time subjects their physical and mental rhythms to a type of behaviour conditioning. He tells you when to eat and drink, since this must fit in with the programme. He certainly says what you must think and how you must feel. This compares very favourably with some of the trendier encounter sessions or est weekends (or even the mediaeval sermon). If you want to get inside someone’s inner defences, all you have to do is stop them head-tripping, release their primal urges and regulate their visits to the loo. The result, says Labour MP and Wagner philosopher Bryan Magee, is ‘to expand consciousness beyond all its normal limits into a total self-awareness…’ Next stop, Wagner and dope.

From the outside, the Bayreuth audience is palpably self-aware – you only have to look at their curdling of European fashion to see that – but it’s hard to think of them getting stoned. They are obviously sharp, rich and bourgeois. Most of them are German; the French are numerous, then comes some Americans and English.

There are white DJs interspersed with black, blue, brown, red, green and silver (one man in a shiny silver suit; one in a track suit). The French are the best and worst dressed: old silk and chiffon gowns or badly cut trouser suits for both sexes with punk crew cuts. Ho, ho I see my dentist in the audience – no, it’s his Bavarian double. There’s an old stiff-backed soldier with a monocle in his eye. Those men in wing collars are from the Paris Richard Wagner Society – the best way to get tickets to Bayreuth in France.

People from 70 nations come to Bayreuth. Booking opens on 24th November but before the end of that month there are five times as many applications as tickets. However, it’s not just a snob festival: ‘Wagner is do demanding of his audience’, says Dr Bauer, the Press Director, ‘that it soon weeds out those who just wish to be seen’, The centenary Wotan, phlegmatic Donald McIntyre, adds ‘If you do come here just to be seen you bloody well deserve to be!’

Does a singer making his pumpernickel and butter out of Wagner understand why the operas get under people’s skins? McIntyre: ‘We adore Wagner because the characterisations are so true. In real life, I know my Hagens and Gunthers and Alberichs, though I am not saying who I think they are, but they exist. Secondly, there are the endless possible interpretations of what are archetypal characters. My part – Wotan/Wanderer/Lord of the Gods – which I’ve done 40 or 50 times – can be played as Hitler, Stalin, Churchill, even as Harold Wilson, or perhaps more exactly, as ex-President Nixon. Third, the dilemma of “The Ring” – power versus love – is universal. All of us would like to chose love but we’re afraid of it while power seems safe and attractive but it’s not. “The Ring’s” a model for ways of life. All the characters try one of the major methods of solving this dilemma, though none succeed. We learn about their mistakes; then it’s up to us. Finally, it’s perfect theatre and only in the theatre can I murder people or sleep with my sister safely or enjoy the only painless way of acting out safely things that are otherwise too painful even to think about’. ‘The Ring’ is therapy addressing the primitive urges. Does the singer feel as moved as the audience?

Do the primitive urges surge through the centenary Brunnhilde, Miss Gwynneth Jones, formerly of Pontypridd Secondary Mod, now an internationally-acclaimed diva? It is highly probably that Ms Jones does resonate with the drama since she is not only one of Britain’s finest sopranos but she is also one of our better actresses. It was Wagner’s intention to marry the arts of music and theatre in ‘The Ring’ and the Patrice Chereau production at Bayreuth with Gwynneth Jones emphatically shows how this should be done. ‘I suppose what people get out of “The Ring” is a kind of ersatz religion. I mean not ordinary Christianity or any other formal religion, they get something which puts them in touch with the essence of religion. I feel this when I am singing “The Ring” or “Parsifal”; the music is so sacred that I sense a great closeness to God, what I call God. By the third act of “Parsifal”, with the Good Friday music I am always crying my eyes out on the stage. The only other thing I ever wanted to do besides sing was to be a nurse helping the sick but I also satisfy the need to help by singing. Some people depend on music and that gives me an enormous responsibility. In Wales, there are lots of marvellous Siegfrieds and Hagens serving at the petrol pumps – they just need a little more single-mindedness. ‘I think the crux of “The Ring” is Brunnhilde’s realisation that only through a kind of harmony in nature can the world survive and this means she has to sacrifice herself. That’s why I was so horrified when a leading Wotan said to me he didn’t think it mattered who got the ring in the end’ even Hagen (the latter villain). As if it didn’t matter whether the Rhine was covered with concrete and the planet poisoned and evil triumphed over good. ‘I live my part on stage except, for example, the time we were still thinking about having a live horse for Brunnhilde and I had to park the animal, walk towards Siegmund very slowly to the solemnest music explaining he had to leave his bride, die and come with me to heaven, and at that poignant moment the horse chose to go to the toilet…’Jokes aside, Ms Jones thinks Wagner basically succeeded in offering a humanistic religion to the masses.

How do Jews, or those with Jewish connections, feel about that? Bernard Levin, for instance, is Jewish and Richard Wagner was violently anti-semitic. Adolf Hitler loved the music of Wagner almost as much as he hated the Jews. Levin says: “We can’t blame Wagner for Hitler…but what have we, to whom his music also appeals, in common with the Fuhrer?’

Screenwriter Robert Levine is also Jewish. He loves Wagner’s ‘Ring’ as much as he detests Nazis. He says he can find ‘nothing anti-Semitical whatsoever’ in the operas. This hasn’t changed the official view in Israel where Wagner’s music remains publicly unplayed to this day. Brian Magee says the actual speaking message of ‘The Ring’ is the total opposite Of fascism: Wagner states: ‘the pursuit of power is incompatible with a life of true feeling’; and ‘the attainment of power destroys the capacity for love’.

The obvious contradiction – that Wagner appeals profoundly to people who are worlds apart politically, spiritually and mentally – suggests an equally obvious solution: his work is primeval and universal. It doesn’t just work at the rational-cerebral level, or even at the level of refined sensibility, it plays to the passions, and we’ve all got those. And it doesn’t just appeal to the good guys; like a catalyst it amplifies your primary drives whatever they are.

Wagner’s music dramas are full of the sort of warnings about living by the sword which Hitler ignored. But empathetically, they are amoral. Thus Levin says ‘Wagner’s “Ring” exposes me to myself for what I am: a wallowing mess of neurosis’ while at the same time making him ‘quite literally drunk’ with pleasure, which proves that Mr Levin, like all good creatures, has a well-rounded personality. This also explains, says Robert Levine, why ‘The Ring’ can be ‘received in a Germanic, racial, anti-Jewish way’, or it ‘can be received even by the Jews as freedom-loving music preaching world peace’.

Brian Wenham, Controller of BBC2, our main opera channel, is a more sceptical Wagnerian (an ‘amateur’, he says) who finds no difficulty in going to sleep after a performance. Time was when he found no difficulty in going to sleep during a performance too but the ‘need for sleep during the opera these days has diminished’. This may be his way of saying he’s actually hooked. ‘I’ve never made a close study of “The Ring” and never made the pilgrimage to Bayreuth and part of me suspects the whole thing might be the most outrageous con – something over the top. But having said that I find myself being drawn to it once every year when I become quite useless for the rest of the week when it’s on’.

Wenham’s close friend Aubrey Singer, in charge of BBC Radio (including Radio 3) is equally emphatic that Wagner does not come between him and a considerable personal stability. But he’s a fan. ‘I like it because of the exciting dramatic scope and total integration of “The Ring”. You hear something fresh in it every time. I’m gripped by the enormous power of what’s the modern Odyssey. You have to admire the sheer chutzpah of the man in making you sit down for that length of time. I’ve no truck with high-falutin’ theories: I’m English and pragmatic. I’d go to Bayreuth like a shot if someone offered me a ticket. I shall go to the Covent Garden cycle again. Meanwhile, I listen occasionally at home. It certainly proves your hi-fi’s working’.

By contrast, Pierre Langbach on his fifth Bayreuth cycle, says ‘Encountering Wagner for the first time was an utter revelation which changed my life. I was not the same person afterwards. The music affects everything inside you from your love-life to your politics. Although Wagner was a pessimist, if one member of the human race can make such music out of pessimism we haven’t lived in vain’.

The Germans naturally have a word for this. The libretto of ‘The Ring’ provides a Weltanschauung or scheme of values, or outlook. For some people, the music also yields a surrogate religion, art therapy or release from sexual tension and taboo. Wagner’s is deeply erotic music (as was his life) and his music dramas are studiously permissive. Magee wonders if they don’t help repressed individuals re-discover their long-lost libidos, not to mention their Ids.

Clearly the work appeals to manic, broken personalities (like Hitler’s) as much as it does to renaissance fellows like Magee and Levin and the rest of us. It’s purgative but indiscriminate; exploring your fantasies may lead you to act them out. It speaks a language of the emotions by definition untranslatable into words.

The only answer to the riddle is personal. I go to Bayreuth because Wagner re-creates in me the memory of my better moments, my worst moments, my loves and hates and lies. It doesn’t do much for my liberation since I don’t feel specially repressed, but it offers an orgy of nostalgia plus some inner strength of more enduring value than last New year’s resolutions. The final curtain of the Chereau ‘Gotterdammerung’ has the entire audience in silent tears as the chorus now massed at the front of the stage turns to face them. The gods have disintegrated in the background. The buck is passed to you. It made me afraid and hopeful for my small son, now four months old, this silent expectant stare from the Gibichung chorus.

No Comments